Semiotic Zombies in Pontypool

Pontypool is the kind of film that gets me excited about the horror genre. It has been described by some as a zombie film, but Pontypool largely ignores many of the conventions of such films to bring something new and fresh to a movie about the “walking dead”

It does this by challenging the zombie film’s stock and trade: guts and gore. Unlike the horde of flesh-eating dead made famous by Romero’s “_____ of the Dead” films, in Pontypool the enemy is unseen. For most of the film we are locked in the claustrophobic church basement where Grant Mazzy and his production team broadcast the news on Radio 660: The Beacon.

That’s not to say the world outside the cold, dark basement of the world is any better. On Grant’s way to work, all we can see is a vast blackness swirled with flecks of snow, a desolate landscape devoid of human habitation or connection. This atmosphere heightens our connection to the characters that run the show, the charismatic Grant Mazzy, the voice of the Beacon; his producer, Sydney Briar and their production assistant Laurel Anne-Drummond, a young war veteran.

A Voice on the Radio

Our intimacy with these characters is as compelling as Grant’s voice on the radio, soft and hypnotic as he tells us about Mrs. French’s cat in the film’s opener. His voice reminds me of late nights I spent listening to the radio as a child, eagerly awaiting the end of Paul Harvey’s “Rest of the Story,” unable to break the spell of the narrator’s velvet smooth voice that wrapped around me like a heavy down blanket. Grant’s voice does the same, reaching out across the blackness to ensnare his listeners and it doesn’t let go.

Mrs. French’s cat has gone missing. “The signs are posted all over town, but no one has seen Honey the Cat,” Grant tells us in a silky voice that sounds like it’s shaking off the last traces of sleep. Interestingly, this is pattern the entire film will follow. Like the search for Honey, signs of the zombie outbreak are everywhere. Funneled into the sound booth, there are the eyewitness accounts from Ken Loney, the traffic correspondent, and independent news reports from the BBC. Trapped, as we are in the basement with the radio crew, we too are unable to see the cat only the signs of its presence.

It is this creepy non-presence of the zombie threat that makes the film so haunting. There are the reports of people being torn to shreds, devoured and dismembered, but we never see any of it firsthand. Like the great storytellers of horror, Pontypool has recognized that the darkest horrors lie in the movie-goer’s imagination and it gives us a mad lib, fill-in-the blank horror film where we supply our own scares.

Shut up or Die

Pontypool also reinvents the source of the “zombie” plague. Rather than blaming it on nuclear power or a devastating virus, Pontypool places its cause in language. The film’s tag line “shut up or die” fits nicely with this new invention. According to the film, certain words are infected and once the infected word is known or understood completely by the speaker it begins the devastating process of annihilation.

As the film’s doctor explains, once a word has infected its victim, that victim begins seeking out another victim to “suicide into.” This explains the mass deaths and the near comical list of endless obituaries that Mazzy reads on the air.

Once infected, the zombies of Pontypool become nothing more than rudimentary radio signals, imitating anything they hear. This includes the sound of windshield wipers, a tea kettle and the spoken words of others as they sound like bats for prey in the dark.

This connection between the infected words and the disease is also a great example of Saussure’s theory of semiotics. According to Saussure, language is made up of a signifier, the word, and a signified, the thing which the word is describing. Together, these two elements make up a sign which is understood across a community. If knowing or understanding the word leads to zombification, then it stands to reason that the un-knowing of a word would be its cure.

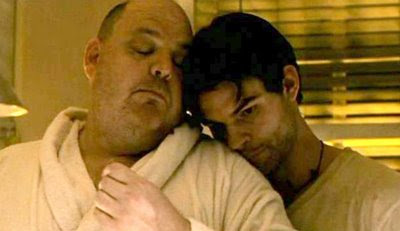

Mazzy discovers that the cure to this bloody hysteria is separating the signifier from the signified, swapping the meaning of one word for another. He finds this when Sydney “gets a bad word,”— kill. She begins saying the word over and over again as the infection takes over. To cure Sydney, Mazzy separates the infected signifier from its signified, the word from its meaning. “Kill isn’t kill!” he shouts jubilantly. He replaces the signified with something else, kiss. “Kill is kiss,” he chants over and over again until Sydney whispers “Kill me” and the two share a passionate smooch.

Despite the discovery of a cure, the dilemma is still the same: “Shut up or die” Do you share the truth at the risk of contracting the disease yourself? At what point does the public’s “need to know” go above the instinct for self-preservation?

These are the questions Pontypool asks and partially answers, leaving much of the interpretation up to its audience, listening captive in the dark.

Comments

Post a Comment