Wolfman in Love

I caught a screening of the much anticipated Wolfman remake while I was attending a conference in Albuquerque this weekend. This latest debut of the werewolf in 21st century cinema seeks to offer fans a more enjoyable, adult alternative to the buff, exploding werewolves of the Twilight franchise.

But while The Wolfman had some decent horror elements (heads, arms and other appendages fly when the lycanthrope gets loose) at its core, it is essentially a romantic pastiche of a horror film. To give an example of what I mean, think Bram stoker’s Dracula by Francis Ford Coppola. While Coppola’s film employs definite aspects of horror (bloodletting and monstrous transformations included) everything is peripheral to the love story between Dracula and his reincarnated beloved, Mina Harker.

The same is true of The Wolfman. Lawrence Talbot returns home after many years abroad to discover the cause of his brother’s sudden and violent death. Once home, he meets his brother’s intended, the beautiful Gwen and his affection for her blurs the line between fraternal duty and personal desire.

There’s a definite connection in the film between the beast within and male sexuality. After Talbot is bitten, his sexual desire for Gwen is more marked, and in one particularly tense scene, Lawrence is mesmerized by her heartbeat and actually growls at her. But this type of male sexual desire is threatening, and to protect her from himself, Lawrence sends Gwen away to London. The werewolf’s violence is also equated with sexual violence, as the detective sent to solve the animal attacks is Aberline, who also worked on the case of Jack the Ripper. This destructive sexual desire is echoed in the figure of Lawrence’s father, who it's revealed killed Lawrence’s brother because he was planning to take Gwen away from Talbot hall forever.

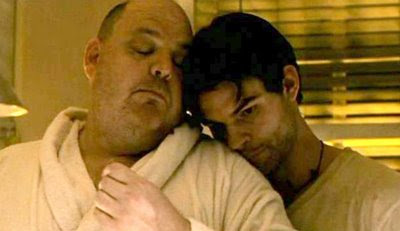

In a film that uses the werewolf as a metaphor for out of control sexuality, it’s little wonder that the film contains so many Freudian references. Freud’s theory of the “primal scene” as observed in (funnily enough) his “Wolf Man” case in 1914 can be applied to the traumatizing death of Lawrence’s mother. Frued theorized that all children either fantasize about their parents having sex or actually see it. Unable to understand the scene, they interpret it as an act of violence while at the same time experiencing sexual excitement. This idea can be applied to the scene where Lawrence comes upon his mother lying dead in his father’s arms, her throat slashed with a razor in her hand. Lawrence later realizes that his mother’s throat was not slashed but torn out by his wolfish father. The trauma of this image has a deferred effect and can cause neurosis in adulthood.

My only complaints come with the film’s saccharine ending and its too fast pace. I felt like I spent an hour and 20 minutes watching 45 minutes of film. The romance between Gwen and Lawrence progresses at a fast clip to make room for the later gore and action sequences in London, but even that felt short. As for the film’s ending, the gypsy Maleva foreshadows that only “one who loves [Lawrence]” can set him free, i.e. bust a silver cap in his wolfish hide. I’ll give you three guesses to figure out who that might be.

Regardless of my earlier complaints about the use of CGI in the wolfman’s transformation, The Wolfman is a viable alternative to the more juvenile werewolves of Twilight and might howl in a new era for the lycanthrope in modern cinema.

Read what others had to say:

Review: The Wolfman (2010)

The Wolfman (2010): Impure In Heart

But while The Wolfman had some decent horror elements (heads, arms and other appendages fly when the lycanthrope gets loose) at its core, it is essentially a romantic pastiche of a horror film. To give an example of what I mean, think Bram stoker’s Dracula by Francis Ford Coppola. While Coppola’s film employs definite aspects of horror (bloodletting and monstrous transformations included) everything is peripheral to the love story between Dracula and his reincarnated beloved, Mina Harker.

The same is true of The Wolfman. Lawrence Talbot returns home after many years abroad to discover the cause of his brother’s sudden and violent death. Once home, he meets his brother’s intended, the beautiful Gwen and his affection for her blurs the line between fraternal duty and personal desire.

There’s a definite connection in the film between the beast within and male sexuality. After Talbot is bitten, his sexual desire for Gwen is more marked, and in one particularly tense scene, Lawrence is mesmerized by her heartbeat and actually growls at her. But this type of male sexual desire is threatening, and to protect her from himself, Lawrence sends Gwen away to London. The werewolf’s violence is also equated with sexual violence, as the detective sent to solve the animal attacks is Aberline, who also worked on the case of Jack the Ripper. This destructive sexual desire is echoed in the figure of Lawrence’s father, who it's revealed killed Lawrence’s brother because he was planning to take Gwen away from Talbot hall forever.

In a film that uses the werewolf as a metaphor for out of control sexuality, it’s little wonder that the film contains so many Freudian references. Freud’s theory of the “primal scene” as observed in (funnily enough) his “Wolf Man” case in 1914 can be applied to the traumatizing death of Lawrence’s mother. Frued theorized that all children either fantasize about their parents having sex or actually see it. Unable to understand the scene, they interpret it as an act of violence while at the same time experiencing sexual excitement. This idea can be applied to the scene where Lawrence comes upon his mother lying dead in his father’s arms, her throat slashed with a razor in her hand. Lawrence later realizes that his mother’s throat was not slashed but torn out by his wolfish father. The trauma of this image has a deferred effect and can cause neurosis in adulthood.

My only complaints come with the film’s saccharine ending and its too fast pace. I felt like I spent an hour and 20 minutes watching 45 minutes of film. The romance between Gwen and Lawrence progresses at a fast clip to make room for the later gore and action sequences in London, but even that felt short. As for the film’s ending, the gypsy Maleva foreshadows that only “one who loves [Lawrence]” can set him free, i.e. bust a silver cap in his wolfish hide. I’ll give you three guesses to figure out who that might be.

Regardless of my earlier complaints about the use of CGI in the wolfman’s transformation, The Wolfman is a viable alternative to the more juvenile werewolves of Twilight and might howl in a new era for the lycanthrope in modern cinema.

Read what others had to say:

Review: The Wolfman (2010)

The Wolfman (2010): Impure In Heart

wow!! This so mad me laugh I love your reviews. You really made me wanna see this movie more but also wait for the dvd at the same time.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete