Takashi Miike Breaks Out of the Box

To be honest, I have never really been able to grasp the complexity or perhaps the simplicity at the heart of Takashi Miike’s films. I first saw Audition at a conference screening and I left the room with feeling of unease and confusion. This same feeling returns to me when I watch Takashi Miike’s Box.

To be honest, I have never really been able to grasp the complexity or perhaps the simplicity at the heart of Takashi Miike’s films. I first saw Audition at a conference screening and I left the room with feeling of unease and confusion. This same feeling returns to me when I watch Takashi Miike’s Box.Box is by far one of the quietist horror films I’ve ever watched. The silence is so profound that for a moment I thought my surround sound was on the fritz. As a watcher of American horror films I am used to being bombarded visually and aurally, whether it’s with a splash of bright red gore or the sickening sound of a knife as it slices through flesh and scrapes the bone. There is none of that here. Miike’s film is placid, almost serene, an environment which makes the events unfolding that much more horrifying.

In Box, Miike tells the story of Kyoko, a young writer who experienced a horrible tragedy in her childhood and has recurring dreams of being buried alive in a box. With the use of flashbacks Miike lays out Kyoko’s life story. She was once a circus performer with her identical twin sister and the two would contort themselves to fit into small boxes. Once locked in these boxes, their guardian Higata would perform a magic trick, turning the girls into white and red chrysanthemums.

In Box, Miike tells the story of Kyoko, a young writer who experienced a horrible tragedy in her childhood and has recurring dreams of being buried alive in a box. With the use of flashbacks Miike lays out Kyoko’s life story. She was once a circus performer with her identical twin sister and the two would contort themselves to fit into small boxes. Once locked in these boxes, their guardian Higata would perform a magic trick, turning the girls into white and red chrysanthemums. But there’s trouble in paradise when Higata rewards Koko’s sister Shoko for her performance with a blue pendant, leaving Kyoko out in the cold. Jealous, Kyko locks her sister in her box as she’s rehearsing for a show. When Higata confronts her, she maims him with a dart and knocks over an oil lamp, setting the stage and the box containing her sister aflame.

But there’s trouble in paradise when Higata rewards Koko’s sister Shoko for her performance with a blue pendant, leaving Kyoko out in the cold. Jealous, Kyko locks her sister in her box as she’s rehearsing for a show. When Higata confronts her, she maims him with a dart and knocks over an oil lamp, setting the stage and the box containing her sister aflame. The only thing I find irritating about Miike’s film is his refusal to explain key scenes in the commentary. I was especially intrigued by the relationship between Kyko and Higata but on this point Miike falls silent. Instead he urges his viewers to “stop thinking so hard” and simply accept what is happening in order to understand. Despite my frustration, I applaud Miike’s artistic prerogative and his refusal to spell out the film for his audience and it reminds me of Ruskin’s struggle when he felt forced to explain the meaning behind his 1853 painting, The Awakening Conscience.

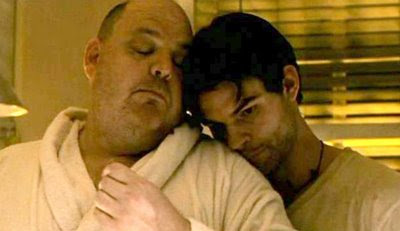

The only thing I find irritating about Miike’s film is his refusal to explain key scenes in the commentary. I was especially intrigued by the relationship between Kyko and Higata but on this point Miike falls silent. Instead he urges his viewers to “stop thinking so hard” and simply accept what is happening in order to understand. Despite my frustration, I applaud Miike’s artistic prerogative and his refusal to spell out the film for his audience and it reminds me of Ruskin’s struggle when he felt forced to explain the meaning behind his 1853 painting, The Awakening Conscience. In the end, Box reveals itself as a short concerned with the split between waking reality and the dream world. Kyoko awakens three times in the film, and it is only the last of these that is a true awakening. As it turns out, Kyoko’s dreams are fantasies of separation from a sister who is attached to her bodily, with Yoshii, a publisher’s representative (who also plays Higata in the film) staring as Higata, the object of desire in her dreams. The clues left by Miike at the film’s start are now clear as we realize why Kyko cannot type and why there are two mugs on her drafting table.

In the end, Box reveals itself as a short concerned with the split between waking reality and the dream world. Kyoko awakens three times in the film, and it is only the last of these that is a true awakening. As it turns out, Kyoko’s dreams are fantasies of separation from a sister who is attached to her bodily, with Yoshii, a publisher’s representative (who also plays Higata in the film) staring as Higata, the object of desire in her dreams. The clues left by Miike at the film’s start are now clear as we realize why Kyko cannot type and why there are two mugs on her drafting table.Miike’s work ultimately represents a departure from the Haunted School of directors like Shimizu (Ju-On) and Kurosawa (Pulse) whose films are centered on ghosts and spectral hauntings. It’s this difference that continues to intrigue me as I explore Miike’s body of work.

Previously: Chan-Wook Park’s Cut and Fruit Chan's Dumplings

Never heard about Box. I might try to see it with friends.

ReplyDeleteRhinehoth a New Horror Novel by Brian E. Niskala