American Imperialism, Vampire Plants and The Ruins

At the very mention of vampire plants most people conjure up the image of Audrey II, the behemoth singing vegetable of the 1986 film musical Little Shop of Horrors, in which Seymour Krelborn, a spineless shop assistant discovers an obscure plant with a thirst for human blood. But Audrey II is just the latest in a long line of vampire plants in fiction, stretching back more than a century to Phil Robinson’s 1881 tale “The Man-Eating Tree” and Fred M. White’s “The Purple Terror,” written in 1898 during the Spanish-American War.

At the very mention of vampire plants most people conjure up the image of Audrey II, the behemoth singing vegetable of the 1986 film musical Little Shop of Horrors, in which Seymour Krelborn, a spineless shop assistant discovers an obscure plant with a thirst for human blood. But Audrey II is just the latest in a long line of vampire plants in fiction, stretching back more than a century to Phil Robinson’s 1881 tale “The Man-Eating Tree” and Fred M. White’s “The Purple Terror,” written in 1898 during the Spanish-American War.Set against the backdrop of this imperialist struggle, British author Fred. M. White crafts a tale of horror and conquest in the heart of the Cuban jungle. West Point naval dandy Lieutenant Will Scarlett must brave the unexplored terrain to deliver a letter from Captain Driver of the Yankee Doodle in Porto Rico Bay to Admiral Lake at Port Anna. His journey will take him into a portion of Cuba dominated by pro-Spanish insurgents where he meets Tito, a man who agrees to guide Scarlett and his entourage to Port Anna. But instead of ensuring their safe passage, Tito leads Scarlett’s party into the clutches of the purple terror, a vampire plant with “weltering purple [orchids]” and a taste for the blood of man and beast.

In White’s story the “purple terror” is a plant known by the locals as the devil’s poppy, a rare orchid equipped with hanging feelers that lies dormant during the day, but at night drops down its massive tentacles to search for its prey. Scarlett and his crew encounter the horrifying proof of the monster plant’s appetite when they come upon a human skeleton caught in a web of the plant’s green feelers “The arms and legs stretched apart as if the victim had been crucified…fragments of [its] tattered clothing flutter[ing] in the…breeze,” and littering the jungle floor are “the skulls of animals and skulls of human beings, the skeletons of birds, the frames of beasts both great and small. It was a weird, shuddering sight”

In White’s story the “purple terror” is a plant known by the locals as the devil’s poppy, a rare orchid equipped with hanging feelers that lies dormant during the day, but at night drops down its massive tentacles to search for its prey. Scarlett and his crew encounter the horrifying proof of the monster plant’s appetite when they come upon a human skeleton caught in a web of the plant’s green feelers “The arms and legs stretched apart as if the victim had been crucified…fragments of [its] tattered clothing flutter[ing] in the…breeze,” and littering the jungle floor are “the skulls of animals and skulls of human beings, the skeletons of birds, the frames of beasts both great and small. It was a weird, shuddering sight”The purple terror represents the allure and the danger of Cuba as a potential imperial possession for the United States. Scarlett is seduced by the poppies as a collector of rare orchids, but at the same time the grasping palpi of the plant represent the danger of embarking on such a mission.

Though White’s story provides a rich reading for British backing of American imperialism, hard scholarship tends to dismiss the vampire plant in literature as an anomaly in vampire fiction that arose when the genre went to ridiculous lengths to revive itself at the end of the nineteenth century. Author Carol Senf mentions vampire plants briefly in her book The Vampire in Nineteenth-Century English Literature but falls short of giving any kind of definitive overview. Senf justifies this omission by identifying the focus of her scholarship on “the vampire as an aberrant human character… [in a study that] does not discuss in any detail the odd variants of the vampire motif.” Her position is shared by literary scholar Christopher Frayling who regards the vampire plant as one of many “bizarre variations [dating] from the 1890’s when the genre had either diversify or repeat itself.”

The dismissal of vampire plants in literature can perhaps be attributed to their origins in the emergence of pseudo-scientific reports testifying to the existence of real vampiric plants in all corners of the globe. These included the published letters of traveler Carl Liche that recount the rituals of a pigmy tribe in Africa who made regular human sacrifices to a tree “shaped like a pineapple…[with] thin palpi” that coiled tightly around the “limbs and body” of its prey and crushed it to death.

The dismissal of vampire plants in literature can perhaps be attributed to their origins in the emergence of pseudo-scientific reports testifying to the existence of real vampiric plants in all corners of the globe. These included the published letters of traveler Carl Liche that recount the rituals of a pigmy tribe in Africa who made regular human sacrifices to a tree “shaped like a pineapple…[with] thin palpi” that coiled tightly around the “limbs and body” of its prey and crushed it to death.Liche’s findings were joined by Dr. Andrew Wilson’s “Science Jottings” that appeared in the Illustrated London News and described the existence of a vampire vine in the swamps of Nicaragua with a “voracious and insatiable [appetite for blood,]”

Due to this tabloid beginning, vampire plants have become an abnormal sub-class in the field of vampire literature—just one of the many weird attractions in the sideshow of turn of the century bloodsuckers that include vampire portraits, houses, mad scientists and even a “winged kangaroo with a python’s neck” As a result they are left to languish in the shadows unstudied compared to their more human counterparts.

One film that has shed some spotlight on vampire plants in recent years is The Ruins. Though the plants of this film are not strictly vampiric and could be classified as more parasitic, their attraction to blood and the imperialistic overtones of the film find strong parallels to White’s 1898 tale.

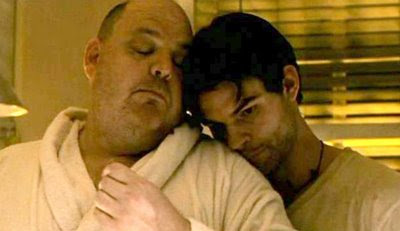

One film that has shed some spotlight on vampire plants in recent years is The Ruins. Though the plants of this film are not strictly vampiric and could be classified as more parasitic, their attraction to blood and the imperialistic overtones of the film find strong parallels to White’s 1898 tale.In the film, a gaggle of American kids and a Greek tourist on vacation in Mexico decide to check out the site of a Mayan ruin hidden deep in the jungle. But once there, the locals make sure they stay put in an attempt to contain the spread of a nasty plant species that lives there. Things go from bad to worse as the plant finds a way into the bodies of its victims and even goes so far as to the snack on the broken legs of one of the tourists.

Like the story, the film takes an imperialist bent with American and European tourists very literally penetrating a Mayan ruin that represents the apex of Mexico’s cultural power.

Like the story, the film takes an imperialist bent with American and European tourists very literally penetrating a Mayan ruin that represents the apex of Mexico’s cultural power.But Scarlett is decidedly more successful with his domination of the purple terror than any of the characters in The Ruins. Having exposed Tito’s scheme to murder the Americans vis-à-vis the purple terror, Scarlett defeats the plant with brute force in an ending that garners sympathy for US imperial activities in Cuba as both necessary and beneficial to its inhabitants.

Further Reading:

The Purple Terror by Fred M. White

The Man Eating Tree by Phil Robinson

Excellent and insightful article Jeanette, never even considered the socio-political implications of the killer plants =D

ReplyDeleteThey can really sneak up on you. Haha.

ReplyDeleteInteresting article - thanks for the historical overview. I wonder how you might theorize the current outcome of these plant movies? Maybe you could call it "postmodern," or perhaps it's more simply a "white guilt" thing? Either way, it seems as though the "good guys" winning is not a popular outcome anymore, and especially in our "green chic" era!

ReplyDeleteHave you seen Long Weekend? It's an Australian film you might find interesting.